(Khapra Beetle)

Background:

The khapra beetle, considered to be one of the world's most destructive pests of grain products and seeds, probably originated from regions now including India and Bangladesh, but has since spread to other areas including northern and eastern Africa, southern Europe and the Mediterranean region, the Mideast, and east into Asia. This pest thrives in warm, dry climates. Populations build rapidly in a short time under hot, dry conditions, but can survive in colder climates in heated situations such as warehouses, food plants and grain storages. The beetle can not fly, and is therefore spread mainly by commerce and trade. The problem of preventing the beetle's spread is compounded by its ability to survive for several years with little food, and its habit of hiding in cracks, crevices and even behind paint scales or rust flakes. If left uncontrolled, the insect can make the surface of a grain storage appear alive with crawling larvae. This species is a considered to be a dirty feeder, breaking or powdering more kernels than it consumes. They not only consume the grain, but may also contaminate it with body parts and setae which are known to cause adult and especially infant gastrointestinal irritation.

Hosts:

In addition to the obvious grain and stored product hosts, the beetle has been found in many locations that would not be obvious food sources, unless one realises that the insect is by nature an omnivorous protein scavenger. It has been found in the seams and ears of burlap bags and wrappers, in baled crepe rubber, automobiles, steel wire, books, corrugated boxes (glue), bags of bolts, and even soiled linen and priceless oil paintings. It is frequently intercepted on obvious food products such as rice, peanuts, dried animal skins, as well as its preferred natural foods such as wheat and malted barley. Such infestations may result from the storage of the product in infested warehouses, by transportation in infested conveyances, or from reuse of sacks or packaging previously used to hold material infested by khapra beetle.

Detection:

Detection may be accomplished by trapping or visual inspection. A khapra beetle trap developed by the USDA is commercially available. When using traps, be aware that a trap will only indicate that the species is present if trapped, but that negative trapping results shall never be used as absolute proof that the insect is not present. Inspecting for khapra beetle is difficult and meticulous due to the small size of the insect, its habits, and the difficulty of identifying small or damaged specimens. High risk areas that should be checked first include: 1) cracks in walls and floors 2) behind loose paint or rust 3) along pallet, and the end-grain of pallet wood 4) seams and ears of burlap bags 5) low light areas 6) trash from cleaning equipment, and the equipment itself. Low risk areas for inspection include: 1) well-lighted areas 2) areas of dampness, moisture, or where debris is mouldy 3) areas that are oily, such as floors. Vacuum cleaners can be used by inspectors to assist the inspector in drawing cast skins or dead adults out of cracks and crevices, and to pick up debris. Vacuum cleaner filters must be changed between inspection locations.

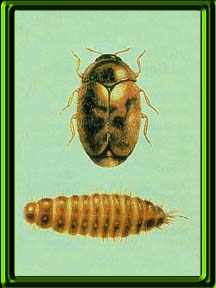

Life Cycle and Description:

The classic telltale sign of a khapra beetle infestation is the presence of cast skins and larvae. The larvae are yellowish to golden brown (see picture below). They are clothed with fine setae, and there are tufts of barbed setae on each side of the terminal abdominal segments. Adults are oval shaped, brown to blackish, and with indistinct lighter brown patterns on the elytra. They may appear slightly hairy on top under a microscope. These hairs may trap dust, giving a dirty appearance. In older adult specimens the hairs may be rubbed off. Mature larvae are about one-quarter inch long, and adult females are about one-eighth inch long with males somewhat smaller. They pass through 4-7 moults during the larval stage, resulting in numerous cast skins. Adults are short-lived, persisting only for one to two weeks, but only for a few days at temperatures over 100°F. Adult activity is seldom noticed. They are more active during midday if the light is subdued, and prefer to avoid the light until they are of older age. Dead adults are not often found since they may be cannibalised by larvae, leaving only fragmentary remains for identification. Mating occurs almost immediately after adult emergence, with oviposition for one to six days following and the female laying up to 80 eggs. Eggs hatch in five to seven days. Larval development may occur in four weeks, but under cooler temperatures, crowding, poor food quality, or frass build-up, the larvae may enter a quiescent condition (diapause). They may persist for months, even as long as one to three years with little or no food in this diapause-like condition. Quiescent larvae may aggregate in large numbers in cracks or other hiding places. They may periodically wander in search of food, but then return to hiding for extended periods.

Treatment:

Fumigation using methyl bromide is the treatment of choice. Because of khapra beetle's habit of hiding in cracks and crevices and infesting porous block, the entire structure, in addition to its contents, must be fumigated. Typically, the building is covered by tarpaulin and the fumigant is pumped in at an approved rate, typically six to nine pounds per thousand cubic feet, depending upon temperature. The process may take several hours, depending on the size of the building and the strict safety precautions required. The future for the continued use of methyl bromide fumigation for khapra beetle is uncertain at this time.

Back to main Stored Product Insect page